Blog Post

Thanksgiving

Regularly cited as American’s favorite holiday, Thanksgiving is celebrated every year on the fourth Thursday of November.

Its popularity is due, for the most part, to the fact that Thanksgiving gives Americans at least two days off work and a very quiet working week, which is primarily spent with family and friends eating turkey, drinking wine and watching American football.

Historically, it is a story of alliance, gratitude and abundance and, although it is commonly considered uniquely American, thanksgiving holidays can also be found on different dates in Canada, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the Netherlands (specifically the city of Leiden within the Netherlands), Grenada, Japan, Liberia, the United Kingdom (the harvest festival) and Brazil.

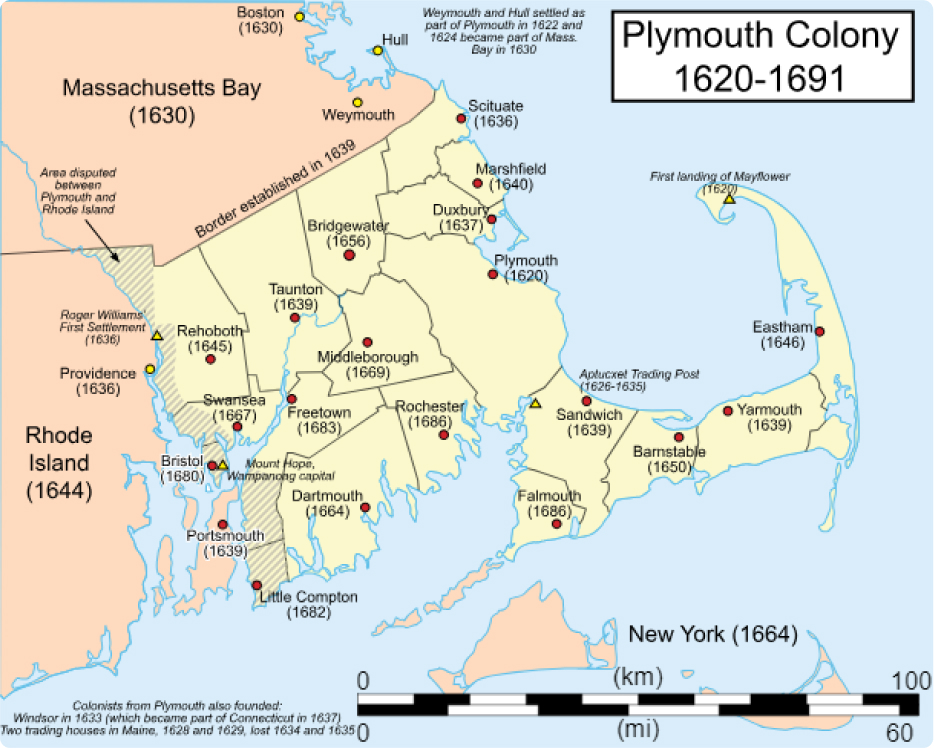

The first Thanksgiving in what is now the United States occurred in 1621, when the Plymouth colonists shared a feast with the Native American people, the Wampanoags. The Plymouth colonists were Separatist Puritans who traveled on the Mayflower from England and arrived in Plymouth in December 1620. 102 passengers landed on the tip of Cape Cod after 66 days at sea and then crossed Massachusetts Bay to set up a colony at Plymouth.

That winter was brutal for the colonists, not used to the bitter New England cold. 52 of the 102 Mayflower passengers died of scurvy, malnutrition and other illnesses leaving only 50 survivors, and when they found an area of cleared land that they could build a village on, they considered it a blessing from God.

This land was, in fact, a Native American village known as Pautuxet where an epidemic of 1616-1619 had killed the 2,000 Wampanoag people who had previously lived there and, before long, they met a Wampanoag survivor called Tisquantum (Squanto).

Squanto was friendly and taught them how to cultivate corn, extract sap from maple trees, catch fish and avoid poisonous plants. He also introduced them to a Wampanoag chief, Massasoit who, during a time of desperate loss and for both parties, made a treaty of alliance with the Pilgrims in return for their help defending against the feared Narragansett tribe.

After the Pilgrims’ first successful corn harvest in November 1621, the governor, William Bradford, invited Massasoit and about 90 members of his tribe to celebrate the English tradition of the harvest festival – a feast which lasted for three days where they ate turkey, venison, goose, duck, seafood, chestnuts, vegetables and cornbread.

This was the pinnacle of good relations between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoags. As the Pilgrim colony grew, it proved increasingly difficult to accommodate the differences between the two party’s ways of life. The colonists persistently encroached onto Indian land and, in 1675, Metacom, who was Massasoit’s second son, went to war against the colonists hoping to drive them out for good.

This was King Philip’s War (also known as the First Indian War) and it claimed thousands of lives and saw atrocities committed by both sides, ending in 1676 when Metacom himself was shot and killed by one of the colonists. Metacom was hung, drawn and quartered and his head placed on a spike and displayed at the Plymouth colony for more than two decades in a precursor to the violent events that would follow between the colonists and the Native Americans over the next two centuries.

George Washington first acknowledged the tradition of Thanksgiving in 1789 when he issued a proclamation for “a day of public thanksgiving and prayer,” and in the middle of the Civil War in 1863, Abraham Lincoln called for the last Thursday of November to be recognized as “a day of Thanksgiving.” Congress passed legislation in 1870, formally making it a national holiday.

Today, parades and rituals are held in cities and towns across the country. The Macy’s department store in New York hosts the grandest parade in New York (the first of which was in 1924), where thousands of spectators line a route through Manhattan and a huge television audience watches marching bands, floats, singers, and performers from home.

Other notable parades are held in Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, Houston and Plymouth itself. Another tradition, that was first pronounced by JFK in 1963 but which fully took hold under George HW Bush, is for the president to pardon one or two Thanksgiving turkeys each year, sparing the birds from the dinner table and sending them to a zoo instead.

As with Columbus Day (which is a federal holiday rather than a national one), Thanksgiving does attract some criticism. On the same day, a National Day of Mourning is held by the United American Indians of New England (UAINE) in Plymouth where people gather around a statue of Massasoit to commemorate the plight of the Native Americans and educate the public on the historical and ongoing challenges they face.

With a similar goal in mind, Native Americans on the west coast hold an “Unthanksgiving Day” on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. Some Native Americans, however, view it positively and compare it to the “wopila” tradition (Lakota for “many thanks”) of the Indians of the Great Plains – an event that can be held by families at any time for reasons as varied as celebrating graduation, sons returning from war, or for someone recovering from illness.

Yet the strong traditions that have developed since its inception have given Thanksgiving its own place in American society. Despite its controversial origins and millions of turkey deaths, it is a holiday that brings more people together than it divides and for that reason alone, is one that should be encouraged and celebrated.