Blog Post

7th December: Pearl Harbor Memorial Day

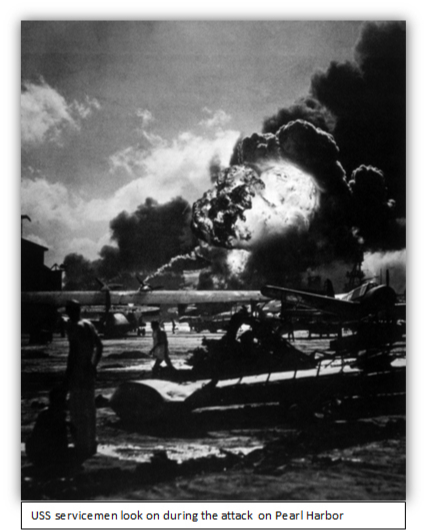

It was on this day in 1941 (7th December) that the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, officially bringing the US into the war. The following day Congress approved Franklin D Roosevelt’s declaration of war on Japan and three days later, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States in what would be a huge turning point in World War Two.

It is easy, these days, to view at the attack as a reckless, crazy gamble, but it was, in fact, almost a century in the making for Japan. Isolated from the west for over two hundred years, Japan was “opened up” when the American commander, Matthew Perry, sailed into Tokyo Bay in 1853 and forced the Japanese to trade with the westerners. Realizing that their armaments were no match for the Americans’ they had no real choice, and they then promptly underwent some serious soul searching as they endeavored to understand how they had gotten to this state and what they could do about it.

Ultimately, they recognized the need to industrialize and embarked on a massive drive to catch up and, hopefully, overtake the Europeans and Americans. Reform-minded military officers reinstalled the emperor as head of state in 1868 (the Meiji Restoration) and, to protect themselves from their neighbors’ expansive tendencies, they went to war with China (1894) and Russia (1904-1905), defeated them both, and annexed Korea in 1910. They next grabbed as many Asian territories as they could that had been previously held by Germany in the wake of World War One, and then invaded Manchuria in 1931, establishing the puppet state of Manchukuo in 1932.

This created an international crisis to which the League of Nations responded by demanding Japan’s withdrawal. But this only drove Japan into leaving the League of Nations itself in 1933 and now, with no international oversight, military extremists took an even more prominent role, and they began pushing into China in 1937, committing terrible atrocities against the Chinese as they went.

Japan signed the Tripartite Pact of 1940 which created a defensive alliance between themselves, Germany and Italy and with the US supporting the Allies, this put them on the other side. Japan imported 94% of its natural resources and by 1940 was specifically eyeing the rice, rubber and tin from British Malaya and the oil from the Dutch East Indies but knew that any invasion of those countries would lead to British and American reprisals. When they advanced into Indochina, Roosevelt froze Japanese assets, embargoed US shipments of oil, and demanded they withdraw. After negotiations with the US failed and Japan’s war minister, General Tojo Hideki, took over as Prime Minister on October 18th, 1941, the chances of withdrawal grew even slimmer.

It was Isoroku Yamamoto, commander in chief of the Combined Fleet and arguably Japan’s greatest strategist, who conceived of the plan to attack Pearl Harbor. He had spent time in the United States learning English at Harvard University and working for the Japanese Navy. He acknowledged the extraordinary industrial capacity of America but considered US Naval officers as nothing more than golfers and bridge players and, inspired by the 1925 Hector Bywater novel The Great Pacific War, he allowed himself to imagine how a hypothetical war with the USA could be won .

Bywater had been a leading naval authority at the time and his fictional account envisioned a Japanese victory over the USA, achieved through a surprise attack on US naval forces, followed up with attacks on Guam and the Philippines. It was remarkably prescient, and when the British launched a surprise attack on the Italian navy at the Battle of Taranto in November 1940, Yamamoto was provided with a template to follow.

The Italian navy had dominated the Mediterranean, providing supplies to Italian forces in Libya and disrupting British supply lines to Egypt to such an extent that the British were forced to sail around the Cape of Good Hope to avoid them. This was unsustainable and, with much of the Italian navy housed in the port of Taranto, they decided on a sneak attack to take out as many ships and supplies as they could. On the night of 11th – 12th November 1940, 21 Fairey Swordfish airplanes set off in two waves from the aircraft carrier, the HMS Illustrious. Flying in radio silence and without navigation lights, they flew for over 170 miles by night and when they reached their destination, dropped torpedoes and bombs on the harbor, hangars and ships below. They took out three battleships, four other ships and caused such damage to the seaplane base and oil depot that the Italian navy never recovered, and the balance of power in the Mediterranean was upended.

Yamamoto had taken notes: maybe such an attack could have the same effect on the United States. America had lived in relative isolation for most of its history, and Japan believed that its people were too weak-minded and creature-comfort loving to go to war, especially if it meant reconquering the whole of the Pacific Ocean, island by island. This was a fatal miscalculation, and an example of how a government could fall for its own propaganda – for while Pearl Harbor was still smoking, Roosevelt called for war, Congress agreed, and the entire US economy was put on a war footing.

The US had seen the results of Taranto for themselves, and suggestions had been made to install torpedo nets at Pearl Harbor to avoid such a calamity. Nothing was done however and, as the day of attack neared, a Japanese message was intercepted on December 6th that inquired about ship movements and berthing positions at Pearl Harbor. The cryptologist’s superior responded that he would revert on Monday 8th December. Then a Japanese submarine was sighted hours before the attack, and a Private noticed a large flight of planes on the radar screen in the morning but was told it was probably just some US B-17 bombers .

The Japanese were in position. For the last ten days, six of their aircraft carriers had been making their way across the Pacific Ocean, having left the Kuril Islands with 414 aircraft and sailing in radio silence for 3,500 miles. They had reached their launch point 230 miles north of Oahu, and on the morning of December 7th, a first wave of bombers set off at 6am. This was followed by a second wave one hour later and radio silence was only broken when the Captain, Mitsuo Fuchida, spotted land at 7.53am, as he declared “Tora! Tora! Tora!” (Tiger! Tiger! Tiger!): code to begin the attack.

In total, eight battleships were hit, including the USS Oklahoma and the USS Arizona. The Arizona exploded after a bomb hit its gunpowder stores, sinking the ship and killing 1,177 of its crew, trapped inside as it sank. The Oklahoma, with 429 men on board, rolled onto its side and sank in the mud. In all, 21 US warships were sunk or were damaged, 328 aircraft were damaged or destroyed, and 2,403 US servicemen and women killed. The attack was over in 75 minutes leaving America reeling in shock. Unconscionable to the Americans, Japan had given no warning or had issued no declaration of war, and FDR commented that December 7th was a day that would “live in infamy”.

Crucially, however, the three American aircraft carriers were not at Pearl Harbor that day – they were out at sea on maneuvers – and the Japanese planes did not have enough fuel to go searching for them. Furthermore, of the eight battleships that were damaged, a huge salvage job followed and all but three of them (the USS Arizona, the USS Utah and the USS Oklahoma) returned to service to play some part in the war.

Japan immediately followed Pearl Harbor up by attacking the Philippines, Guam, Midway Island, Wake Island, Malaya and Hong Kong and, contrary to Japan’s hopes and beliefs, the US were not prepared to let any of this slide. The US demonstrated their ability to bomb Tokyo with the Doolittle Raid of 18th April, 1942 (which brought vicious reprisals from the Japanese on the Chinese), and the Americans fully began turning the tide with the Battle of Midway in June, 1942. They underwent their first major amphibious landing on Guadalcanal in August 1942 and finally took control of the island of Okinawa in June 1945 in one of the bloodiest battles in all of human history, as they prepared to invade mainland Japan.

Roosevelt had hoped to avoid war – indeed he had promised to keep Americans out of it during his election campaign of 1940 (although privately he acknowledged how difficult that would be). But this promise was summarily ditched after Pearl Harbor, and the whole tragedy only came to an end after two atomic bombs had been dropped on Japan, forcing it into surrender on September 2nd, 1945.

There are many lessons we can take from Pearl Harbor: be alert to a surprise attack, be careful who you trust and, most importantly, stay unified. The Japanese assumed that the US citizens would roll over, but Americans disproved said notion as they mobilized huge amounts of resources, engaged with enemies the world over and, crucially, come out much stronger on the other side.

Citations:

“Navy | Military Force | Britannica.” Accessed December 14, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Yamamoto-Isoroku.Imperial War Museums. “Why Did Japan Attack Pearl Harbor?” Accessed December 14, 2022. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/why-did-japan-attack-pearl-harbor.WW2 Museum, NO, LA. “Pearl Harbor Fact Sheet.” National World War II Museum, New Orleans, LA, n.d. file:///C:/Users/csero/OneDrive/Documents/History%20in%20a%20Heartbeat/Blogs/Pearl%20Harbor/Pearl%20Harbor%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf.